The Story behind the Stone – the families, estates and stories of Kirkmichael, Cullicudden, the Black Isle and beyond

Gilbert Macculloch, teacher in Jemimaville and Superintendant of the Royal Blind Asylum and School, Edinburgh

text: Dr Jim Mackay photography as set out below each image

This is the story of the Resolis origins of Gilbert Maculloch (1812–1886), who began his career as a teacher in Jemimaville and became a highly respected teacher of the blind, an author of religious tracts and the Superintendant of the Royal Blind Asylum and School, Edinburgh.

His grandfather, blacksmith, Gilbert McCulloch (1745–1821), is commemorated on a slab which lies below the turf within the McCulloch burial area of Kirkmichael, the inscription of which he shares with his son and nephew.

Gilbert Macculloch’s memorial in Kirkmichael; photo: Davine Sutherland

Gilbert McCulloch (1745–1821) and his wife Margaret Hendry

Our story starts with Gilbert the blacksmith, born in Ferryton, parish of Resolis, in the year of the second Jacobite rebellion. We can assume he was named, like many other children in this era, after the distinguished Cromarty minister Gilbert Anderson of Udale. Gilbert’s parents were George McCulloch and Jean McCulloch who feature in the related Story “Two Centuries of McCullochs in Resolis”. Gilbert’s son Frances was a Resolis blacksmith journeyman who spent some time in Edinburgh, where young Gilbert was born.

Gilbert married Margaret Henry or Hendry, and from the baptism records of his children we can tell he was located at Newhall as a blacksmith for a long time. There were Hendry families in the area, but there is nothing to indicate which family Margaret belonged to.

Resolis baptism records for the couple were George (1778), Katharine (1780), twins Cathrine and Jean (1783), son Frances (1785), Charles (1789) and Gilbert (1791). Whilst he is recorded as smith or blacksmith “Newhall” in all these baptisms, he is listed as “at Burnside” in the 1798 Militia List of adult males aged between 15 and 60 years, and it may be that “Burnside of Newhall” was a more accurate location for him. Whichever, he had relocated to Gordon’s Mills by 1816 as he features on “Rental of Newhall’s New Property as at Martinmas 1816”, his rental recorded as £10 at this time, also the case on the 1818 Rental. He died, according to the slab in Kirkmichael, on the “5th day of March 1821 aged 75 years”.

Here lies the body of / GEORGE McCULLOCH who / died August 8th 1786 / aged 28 years / To the memory of / JEAN McCULLOCH who died / upon the 10th day of April / 1810 aged 27 years And / also GILBERT MCULLOCH who / died 5th day of March 1821 / aged 75 years

The ages and years on that slab were very puzzling until we realised that the George commemorated upon it was his nephew whilst the Jean was his own daughter, born 1783, died 1810 and hence aged 27. I do wonder if his nephew had been “farmed out” to Gilbert‘s family as I have found on other stones “adopted” children being commemorated on the memorials of the adopting family.

Frances McCulloch (1785–) and his wife Mary Munro (–1840)

Son Frances (baptised 9 November 1785) became a smith like his father, but he travelled much more widely. He married in Resolis in 1806:

29 July 1806 Francis McCulloch in this parish & Mary Munro in the parish of Roskene were contracted and married in due time

The birth of Gilbert we pick up in Edinburgh:

1812 … Feby. 1st. Francis McCulloch smith & Mary Monro his spouse College Church Parish a son born 2d. Jany. last named Gilbert

Although they were in Edinburgh in 1812, Frances and Mary returned to the Black Isle where the poorly-kept baptism records of the time record at least several of his children:

Resolis Baptism Register

5 October 1815 Francis MacCulloch blacksmith Gordons Miln & Mary Munro – George

14 September 1817 Francis McCulloch smith Balblair & Mary [not given] – twins John & Isobell

31 August 1820 Francis McCulloch at Gordon’s Mills & Mary Munro – Jane 25 Aug

13 Aug 1823 Francis McCulloch blacksmith at Gordon Mills & Mary Munro – Charles 3 Aug

The first sign that Frances was not just any smith comes from an item in a roup of 1823. Distiller Duncan Montgomery at Poyntzfield had been made bankrupt and all his possessions were sold. Ploughs, mirrors, hoes and carpets were all picked up by local worthies, but Frances bought just one lot:

Frances McCulloch Gordens Mills – a Lot School Books -.-.10

Why would Frances be buying school books? His son Gilbert at this time would be 11 years old and no doubt this purchase helped to set him on his future career.

I think at the time of the death of the wife of Frances, Mary Munro, the family may have moved to Cromarty, as her death is recorded in the Cromarty records though she is buried in Kirkinchael:

1840 Cromarty Burials

15 Jun Mary Munro, or Maculloch, burried at Kirkmichael 9/-

Despite being buried in Kirkmichael, Mary does not appear on any of the extant inscriptions within the McCulloch burial area. There is no mention of her husband Frances on any stone there either. I do wonder if a slab was broken up to make way for a later memorial.

Gilbert McCulloch (1812–1885) and his wives

Agnes Gray Moxey (1806–1861) and Alexandrina Macleod Fraser (c1822–1909)

In 1876 the premises of the Royal Blind School moved to this much larger, custom-built building, designed by Charles Leadbetter, off Craigmillar Park in the south of the city of Edinburgh, merging with the 1835 School for Blind Children. Gilbert MacCulloch became Superintendant of the combined institute, the curriculum of which at this time had extended to cover arithmetic, Braille printing, English, geography, history, recitation and even the elements of geometry, while older children were given instruction in organ and piano playing. Photo by Lokal_Profil published under Creative Commons licence

I note that young Gilbert showed some academic prowess at school through a long item in the Inverness Courier of 14 June 1826 when Cromarty teacher Mr Macleod invited local gentlemen in to inspect the school and quiz the pupils. Gilbert appears in the prizes for the Latin class, although I note the reporter considered the Latin class not very far advanced!

Examination of Mr Macleod’s School at Cromarty… The next class, if we remember right, was one at Cornelius Nepos. The brief space these had been studying Latin precluded the possibility of great proficiency in the language. Their time, however, had been well employed. Their progress up Parnassus was indeed small – but their footing sure. Their intimate acquaintance with Ruddiman’s celebrated chap. ix. pleased us much.

…

The following is the order of Distribution:–

Cornelius Nepos.– James Taylor, Gilbert M’Culloch, James Andrews, James Grigor.

In time young Gilbert became a schoolmaster himself, a well-respected schoolmaster. The Reverend Donald Sage, writing in 1836 for the second Statistical Account, says of the school and schoolmaster in the east end of the parish of Resolis:

The other school is at the village of Jemimaville. This is one of the Assembly’s schools, taught at present by Mr Gilbert M’Culloch, and is certainly one of the most efficient and best taught seminaries in the north. The intellectual system has been adopted, and with great success. Many young men taught at this school are now the teachers of subscription schools through the country, very much to the satisfaction of their employers.

At this time the role of the schoolmaster was closely associated with the church. I note from the Kirk Session Minutes of 4 August 1838 that on the list of Male Heads of Families in full communion with the church appears:

Gilbert McCulloch Schoolmaster Jemima Ville

He appears on the same Roll in 1840 and 1841 and that year we find him recorded in 1841 at the old family home of Gordon?s Mills, in company with sister Isabel and brother Charles:

1841 Census Record Gordons Mills, parish of Resolis

Mr Gilbert McCulloch 28 Schoolmaster

Isabel McCulloch 20

Charles McCulloch 14

I wonder if he still held the books his father had bought back at the roup in 1823? Gilbert had further ambitions, and to start with he was headed for larger schools. The Kirk Session minutes for 11 July 1842 state that:

The Roll of last year (1841) having been read coram & the session find that since the dispensation of the ordinance in August 1841, Gilbert McCulloch, Teacher, Jemima Ville had left the parish

He was for a period teacher at Rosemarkie. In 1843, of course, occurred the great Disruption, when the majority of parishioners in the North of Scotland left the Established Church to join the newly formed Free Church. Two of the great ministers of the new church were the Reverend Donald Sage of Resolis, where Gilbert had just left, and the Reverend John Kennedy of Dingwall. It was whilst Gilbert was teaching at Rosemarkie that he married his first wife, and the officiating minister was none other than the great John Kennedy himself:

Inverness Courier 29 October 1845

At Dingwall, on the 23d inst., by the Rev. John Kennedy of the Free Church, Mr Gilbert M’Culloch, Teacher, Rosemarkie, to Agnes Gray, eldest daughter of the late Captain Moxey, R.N., Libberton Cottage, Edinburgh.

Agnes had been born way back in 1806, in the Parish of Innerwick, close to Dunbar. Black Castle was a Napoleonic coastal Signal Station.

Baptisms, parish of Innerwick

At Blackcastle Signal Station 30 Novr. 1806 Agnes Gray born 20th inst. daughter to Lieut. Benjamin Solomon Maxey [sic] and Mrs Jane Todd his wife witnesses James Todd and John Gray

Gilbert and Agnes were to move again soon. Gilbert’s brother George was working in Aberdeenshire for the railway at this time and it was to Aberdeenshire where Gilbert was headed himself as a teacher. We pick him up in 1851 at the Little Square, Oldmeldrum, as the teacher of the Free Church School there.

1851 Census Return for Little Square, Old Meldrum, Chapel of Garioch, Aberdeenshire

Gilbert McCulloch Head Married 39 Teacher Of Free Church School born Edinburgh

Agnes McCulloch Wife Married 44 born Dirleton, Haddingtonshire

Agnes G Morison Niece 11 Scholar born Dingwall

Margaret Cameron Unmarried 21 Servant born Berwickshire

You will note the niece in the household, one Agnes G Morison, born in Dingwall. Her parents were John Morrison and Jane Todd Moxey, so you can see some of the same family associations as in the Innerwick baptism. Lieutenant Moxey of Blackcastle Signal Station was to become Captain Moxey of the Royal Navy.

It was in this period that brother George, along with wife Mary Brown, and their many children, emigrated to Canada, there to continue his employment within the railway industry.

Memorial commemorating George Macculloch and Mary Brown in Southgate Cemetery, GreyCounty, Ontario

There were to be no children of the union of Agnes and Gilbert but the couple were deeply devoted to each other. It was whilst he was at Oldmeldrum that Gilbert had some success in publishing religious tracts. In consequence, he was invited to join the Stirling Tract Enterprise, and moved there with Agnes.

1861 Census Return – Port Street, Stirling

Gilbert Macculloch Head Married 49 Religous Literature born Midlothian

Agnes G Macculloch Wife Married 54 born Dirleton, Haddingtonshire

Margaret Cameron Servant Unmarried 18 Domestic Servent born Argyllshire

Gilbert was involved in religious and moral initiatives, and the Stirling Observer often referred to him positively. By 1863, he had become the editor of a religious magazine, as I note the Banffshire Journal of 7 April 1863, when listing the elders of the Presbytery of Forres at the Assembly mentioned: “Gilbert M’Culloch, Editor of Gospel Trumpet, Stirling”.

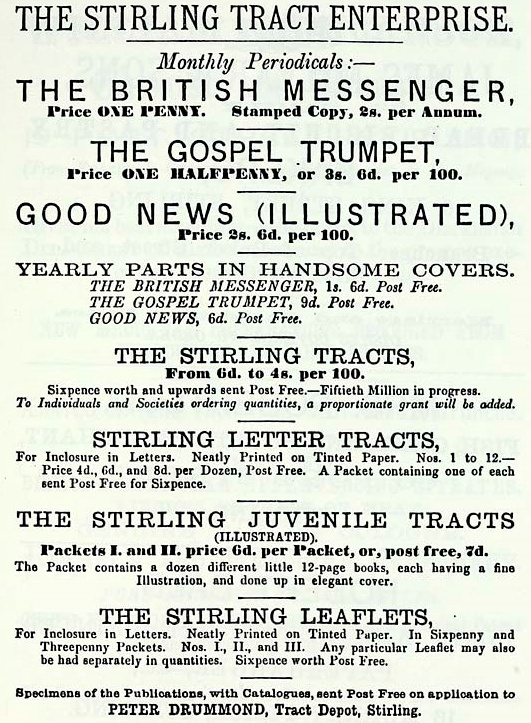

The publications of the Stirling Tract Enterprise, including the Gospel Trumpet

Late that year Agnes died, and the following touching tribute was published in the Stirling Observer of 2 January 1862:

Macculloch.– At 42, Port Street, Stirling, on the 29th ult., Agnes Gray Moxey, eldest daughter of the late Captain B.S. Moxey, R.N., Liberton, near Edinburgh, and wife of Mr Gilbert Macculloch, of the Stirling Tract Enterprise, and late Free Church Schoolmaster, of Old Meldrum, near Aberdeen. To a finely-constituted, and well-cultivated mind, which long-continued bodily affliction had brightened rather than impaired, she added a cheerful, loving, and amiable disposition, which endeared her much to all who knew her, and could appreciate her worth.

The following year the same newspaper published the notice of Gilbert’s second marriage:

Stirling Observer 9 July 1863

Macculloch – Fraser. – At Bondgate Chapel, Darlington, on the 2d inst., by the Rev. Henry W. Jackson, Mr Gilbert Macculloch, Stirling, to Alexandrina Macleod, youngest daughter of Mr D. Fraser, Ullapool, Ross-shire, and niece of the late Rev. Alexander Macleod, one of the ministers of Cromarty. (No cards.)

I note that Gilbert whilst in Stirling was still in 1863 acting as an elder for the Free Church Presbytery of Forres (Inverness Courier, 9 April 1863, reporting on the Members of Assembly).

In order to supplement his income, Gilbert became an agent for the Scottish National Insurance Company, whose advertisements were featured in the Stirling Observer as well as mention of his religious activities.

His address remained as 42 Port Street, Stirling, for many years. This distinctive corner building still stands, the bottom floor occupied by many retailers over the years.

Stirling Observer, 11 May 1865

42 Port Street, Stirling; courtesy of Historic Environment Scotland

Gilbert and Alexandrina were blessed with two children, daughters Mary Alexandrina Macculloch (1864–1945) and Agnes Bertha Isabella Macculloch (1866–1947).

But between the births of the two daughters, Gilbert had made quite a dramatic leap in employment. Again, the Stirling Observer, of 30 November 1865:

Eastern Border Mission to the Blind.– We understand that Mr Gilbert Macculloch, who has been long and favourably known here, and throughout the district, from his connection with the Stirling Tract Enterprise, and otherwise, has just accepted the appointment of the above benevolent and very interesting Mission. Mr M. is also favourably known as the author of some useful little works, on moral and religious subjects, and is, besides, the compiler of the Directory and Guide to Stirling and neighbourhood, recently published. The Border Mission, we believe, has been in existence for some time, and is conducted on Moon’s system, which, from its admirable simplicity, and the ease with which a complete knowledge of it may be acquired, has been found such a boon to that afflicted portion of the community. We congratulate the Mission on having secured Mr Macculloch’s services. In entering on this new sphere of labour, Mr. M., we doubt not, has found something congenial to his taste, and in taking his departure from Stirling, we are sure he carries with him the good wishes of all who have the pleasure of knowing him.

To quote Ian Hutchison in his “The Value of a Flawed Source: The Register of the Missions to Outdoor Blind for Edinburgh, the Borders and the Lothians, c.1903–10” (

Missions to Outdoor Blind were established in Scotland from 1857, the first such Mission serving Edinburgh, the Scottish Borders and the Lothians. … When the society was first formed, its mission was firmly focused on teaching blind people, living in the community, to read tactile print. In the decades that followed, its objectives gradually expanded beyond this initial raison d’être.

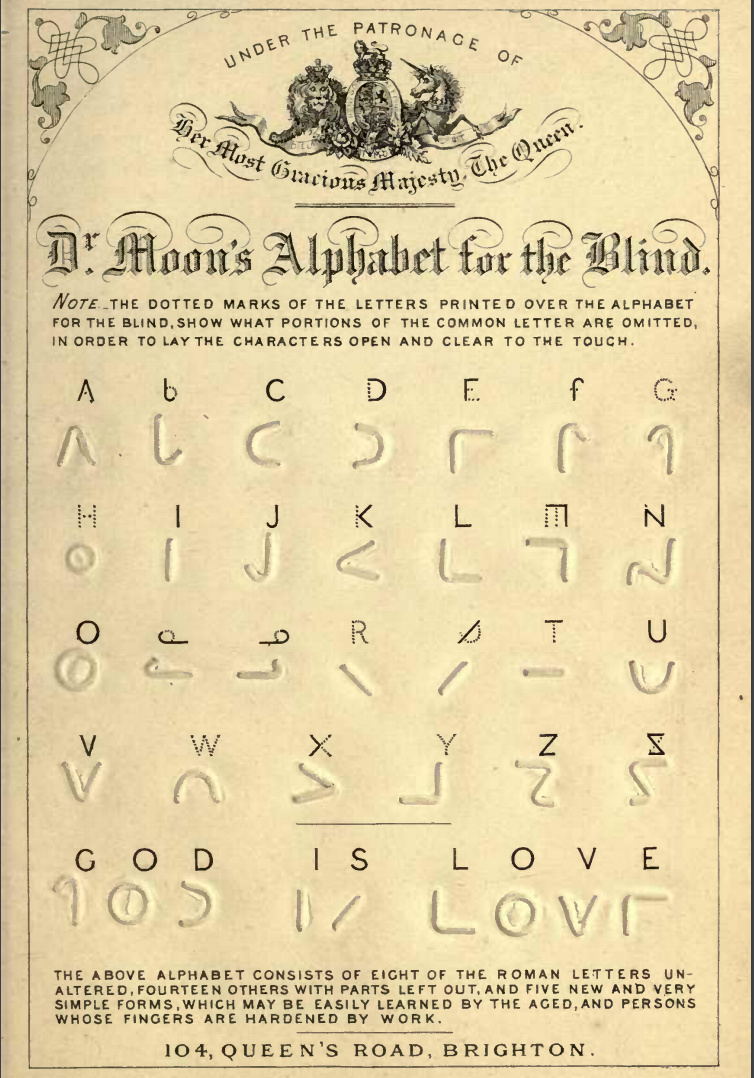

This expansion included going out into the community to assist the blind to read tactile letters. There were various forms in use, but the most popular nationally was that developed and promoted by William Moon of Brighton, himself blind, in the 1840s.

The simplified raised lettering of the Moon Code, created in the 1840s, is still taught nowadays, and is particularly useful for those with less sensitive fingures; image courtesy of AtlasObscura.com

Cover of “Feeling Our History”

I note, that though the 1865 article in the Stirling Observer suggested he was leaving Stirling at that time, when his second daughter was born in 1866, the address of the family was still 42 Port Street, Stirling.

Gilbert’s next step in helping the blind, combined with his experience as a teacher, was in running a school for the blind. The 1871 Census shows that he had by this time moved to Edinburgh where he was residing as Superintendant of the Edinburgh School for Blind Children, then located at 2 Gayfield Square. He was supported by his wife, Alexandrina, as Matron, a cook, nurse, housemaid and pupil teacher, and his own two daughters were in household. There were 32 boarding scholars, of both sexes, from 9 to 15, from locations as widely dispersed as Orkney and Cheshire, although quite a number were from the Edinburgh area. One of the children resident was 11-year old Robert Edgar, who is recorded as “Blind & Deaf & Dumb” and would later feature in a publication by Macculloch.

A recent publication “Feeling our History. The experience of Blindness and Sight Loss in Edwardian Edinburgh, the Lothians and the Scottish Borders” by, again, Iain Hutchinson (RNIB, 2015) states:

In 1851, property at 2 Gayfield Square was purchased for £900 and this served as Edinburgh’s blind school for the next 25 years. In 1867, there were 34 children on the Gayfield Square school roll. Also living on the premises were a superintendent and a matron who both taught the pupils alongside their other duties. In 1876, the school joined with the blind asylum which then became the Royal Blind Asylum and School, located in new accommodation at Craigmillar. In 1911, the school had 43 pupils.

During this period Gilbert published a very well received short book entitled “Story of a Blind Mute: Who Died in the Royal Blind Asylum and School, Craigmillar, Edinburgh, March 6, 1877, in the Sixteenth Year of his Age.” When republished in 1881, the Christian Week published the following review:

To quote from MacCulloch himself, he had thought previously that he considered blind people to be ‘not religiously inclined’. He had been told by one blind man that the Bible was ‘a matter of moonshine,’ and Gilbert believed ‘that sentiments of the kind are by no means uncommon among his class’. He was reluctant to admit nine-year-old deaf-blind Robert Edgar to the Blind School because of his deafness. When Robert was also rejected by the Edinburgh Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, on account of his blindness, Gilbert agreed to admit the boy ‘as an experiment’. He then found, to his great pleasure, that Edgar was intelligent, hard-working, and had strong religious devotion.

It has been said that circulation of Gilbert’s small publication did more for support of the blind than voluminous Reports! In that same year of 1881 when his expanded book was published, Gilbert and Alexandrina are shown in the Census as now being the Superintendant and Matron of the new combined institution. Their two daughters are still in residence. There are far more residents, of all ages. It must have been a very challenging post given the few staff involved.

Royal Blind School, Craigmillar Park, Edinburgh

Sadly, Gilbert died a few years later, on 5 January 1885, of that dreaded disease of the time phsisis or tuberculosis. His daughter Mary, who informed the Registrar, called him simply “Teacher, Retired”. His death was noted in many of the newspapers of the time. A sympathetic obituary was included in the paper which had been so supportive of him whilst he resided in Stirling, the Stirling Observer, of 7 February 1885.

The Late Mr Gilbert Macculloch.– In the beginning of last month there passed away quietly at Edinburgh a gentleman who, from his former connection with this district as well as for other reasons, deserves a passing notice in these columns. We refer to the late Gilbert Macculloch, formerly teacher of the F.C. School, Oldmeldrum, and thereafter connected with the Stirling Tract Enterprise. Mr Macculloch was in many respects a remarkable man. A native of Cromarty, we believe, he was mostly self-taught. His literary ability was of a high order, as his numerous publications, received by the reading public with the greatest acceptance, testify – such as “Profession and Practice,” “The Banished Minister,” “The History of a Deaf Mute,” &c., &c. It was a prize essay on the Sabbath that first brought him into notice; and so much was the editor of the British Messenger, the Rev. William Reid, and the late Mr Peter Drummond, taken with his literary ability, that he was invited to Stirling as a collaborateur. Leaving Oldmeldrum he took up his abode at Stirling, where he remained a good many years as editor of the Gospel Trumpet. Eventually he was appointed superintendant of the Royal Blind Asylum, where he did yeoman service toward extending and consolidating that flourishing institution. It was while thus occupied that he wrote the interesting tractate about the deaf mute referred to above, and which, if we mistake not, attracted the notice of Royalty itself. He was a man of eminent piety, much beloved by his pupils and by all who knew him. His handwriting was peculiarly neat and beautiful. He was a teacher before the Disruption, but cast in his lot with the Free Church, which he loved so well, and of which he was an honoured office-bearer. He leaves a widow and two daughters.

Alexandrina and her two daughters remained together, first in Argyle Place, in Edinburgh, and then in Coupar Angus, where Alexandrina died in 1909. Her daughters lived to a good age and never married. Mary became a governess and then a private school teacher, whilst Agnes was for a time a musical governess and then a music teacher. They lived for a long time in Blairgowrie Road, Coupar Angus, but they are both buried in Dean Cemetery in Edinburgh, a burial ground with many Resolis connections.

The Entrance to Dean Cemetery, Edinburgh; image courtesy of GravestonePhotos.com

The serried ranks of headstones in Dean Cemetery; photo by Jim Mackay

Memorial to Gilbert MacCulloch and family in Dean 2a Cemetery, Edinburgh; photo courtesy of GravestonePhotos.com