The Story behind the Stone – the families, estates and stories of Kirkmichael, Cullicudden, the Black Isle and beyond

Charles Regnart (1759–1844)

text: Alastair Morton Kirkmichael photos: Andrew Dowsett

On the east wall of the Gun Munro mausoleum at Kirkmichael there is a striking monument to George Gun Munro of Poyntzfield who died on the 2nd of July 1806. He was the gentleman who had had the kirk’s nave truncated and partly rebuilt as a mausoleum for his family’s burials.

The masterful Charles Regnart memorial for George Gun Munro of Poyntzfield, who

died in 1806

Back in September 2015, when a work party of volunteers were clearing the inside of the kirk, we were struck anew by the quality of design and artistry of the memorial. Once the debris of the collapsed roof had been sufficiently removed a sharp eye spotted that there is a signature right at the base of the memorial. It reads :–

C. REGNART FI.

Hampstead Road

LONDON

We then realised that this memorial was in a different league from most of the others in the kirk, which reflect local design and manufacture: this was a more cosmopolitan style.

To be fair, for many years the memorial could only be seen by torchlight, after a struggle to pull yourself through the window (the only access), and it was completely covered by grime. As the years went by, and more holes appeared in the roof, access became easier, although more perilous!

The memorial in days gone by

Now realising we had something special, we turned to the internet. Research on the net revealed that Charles Regnart was a monumental sculptor of some repute who worked mainly in London and the South East of England. He has been described as “an extremely competent monumental mason whose work may be found all over England.” and “Regnart was far above the commonplace mason-sculptor in talent, and most of his monuments have significant decorative carving upon them, ranging from low relief ornaments to high relief pots and urns, to full figure sculpture”.

His masterpiece is considered to be the altar tomb with a recumbent figure of George Rush at Farthinghoe. It depicts Rush as “an old, old, man, thin and emaciated, clad in a loose robe with slippers on his feet and his Bible in his hand … at the point of death”, his eyes gazing towards heaven.

photo: © Rex Harris

This effigy is described as “one of the most remarkable and unusual executed in Britain during the early nineteenth century”. Regnart exhibited the tomb chest and a model of the figure at the Royal Academy in 1806.

Regnart was born in Bristol in 1759, married twice, and died on 19 November 1844. He was himself buried in the Hampstead Road cemetery in London, and it would be interesting to see what memorial graced his tomb!

It is believed that he started his sculpting career by 1791. He came from a line of sculptors. His father, Philip Regnart, was known in his own right as a “carver and gilder” and had started work under his own father, also a sculptor.

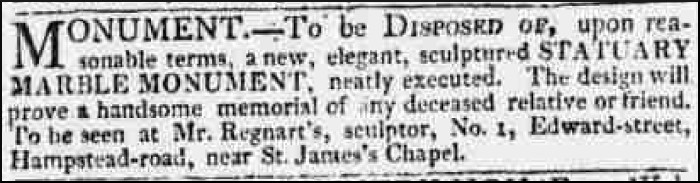

Philip became bankrupt in 1805 and was then living in Cavendish Square, London, close to his son’s residence in Cleveland Street. It is suggested on the web that Charles Regnart moved to a house in Hampstead Road only in 1817, after his second marriage, but this is incorrect, as we have located an advertisement in the Morning Chronicle for 3rd May 1814 giving his address as No. 1 Edward Street, Hampstead Road.

The advertisement is itself is elegantly worded:

A typical Charles Regnart advertisement, from 1814

It seems likely that the Gun Munro memorial was not completed until several years after George Gun Munro’s death in 1806.

You can follow up Charles Regnart on several websites:

http://www.speel.me.uk/sculpt/regnart.htm

http://217.204.55.158/henrymoore/sculptor/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=2239

http://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Regnart-38

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Regnart

http://www.victorianweb.org/sculpture/ternouth/1.html

and a series of superb photographs by Rex Harris can be found at https://www.flickr.com/photos/sheepdog_rex/14802098370/in/photostream/

We are used in Kirkmichael and Cullicudden to seeing the symbols of mortality common in Scottish graveyards: the gravedigger’s tools, the hourglass, the dead bell, the coffin. In the design of the memorial in Kirkmichael, Regnart has used several common symbols used on memorials of the gentry, and typically English gentry, and has executed them beautifully and masterfully.

The snake biting its own tail, or ourobouros, is a symbol of eternity and thus an emblem of immortality, as is the burning torch which it curls around. The willow fronds are designed to dispel evil, purify and facilitate contact with the spiritual world. The lopped branches point to a life cut short.

The urn, symbolising death, is clasped by Psyche indicating the love of the deceased’s relatives. The beautifully carved lilies are suggestive of purity and innocence, the symbol of Our Lady.

The carving of the snake’s head is perhaps not so masterful – Regnart had clearly never seen a snake up close, ending up with something more akin to a swan!

It is interesting to ponder on how Regnart came to be commissioned by the Gun Munro family to design and create the memorial to George, to be installed so many hundreds of miles from his usual area of work. As set out in “The Same Sculptor?” Story Behind the Stone, the Gun Munro family were closely associated with the Davidson family of Tulloch, who had commissioned earlier work by Regnart.

It is doubtful if Regnart ever visited Kirkmichael in person. The memorial would have been created in a number of pieces and shipped north, to be assembled and installed by local craftsmen.

The Georgian Regnart memorial in the Gun Munro mausoleum in Kirkmichael

To the best of our knowledge, the Kirkmichael monument is by far Regnart’s most northerly sited piece of work, and, we believe, one of his finest.